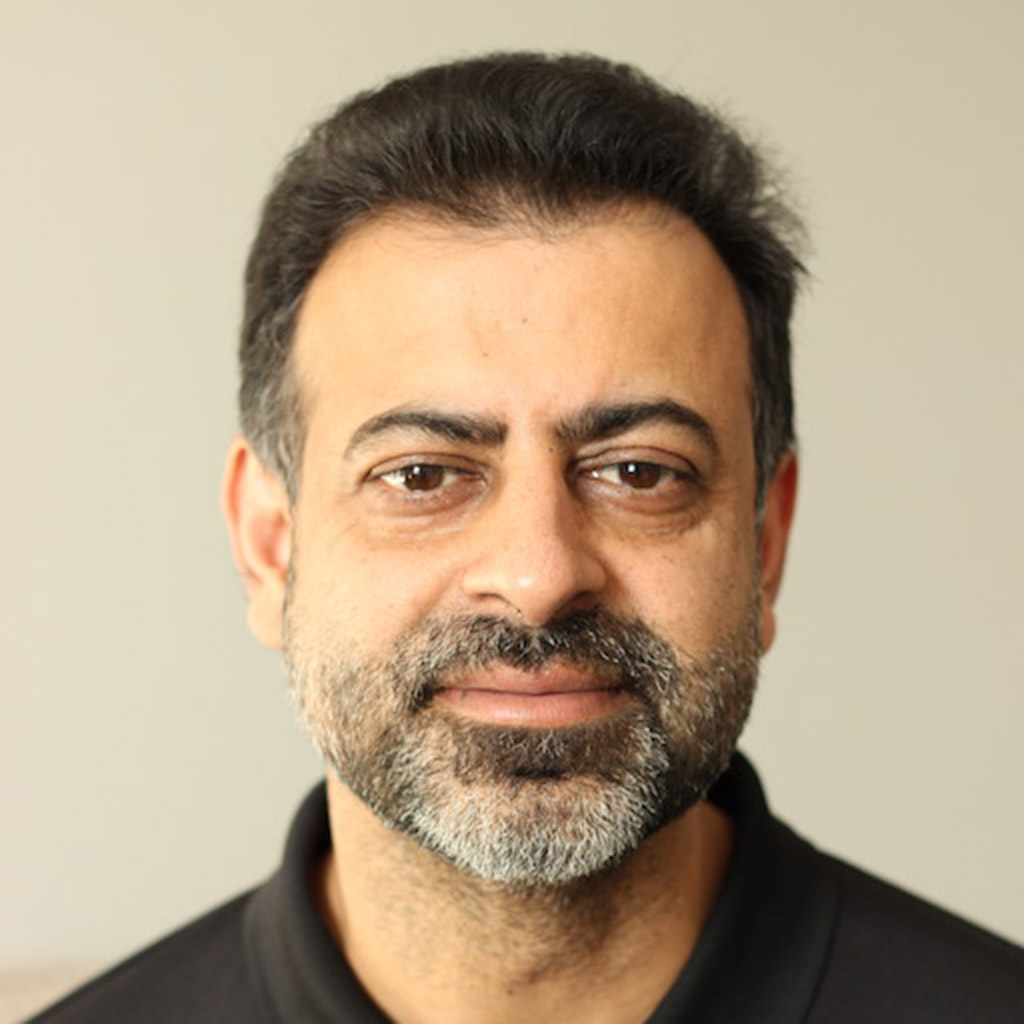

Suzanne: So, most interesting place today, maybe perhaps for this whole project so far. You seem to be the most international candidate. Born in Spain?

Jacobo: That’s right.

Suzanne: Studied in London. What are you doing in LA?

Jacobo: I came to LA about 18 months ago now. I initially came to help a guy called Keith Ferrazzi build his software company. It’s called Yoi. The company does human capital management. Keith’s brought me over. At the time, I was in Philadelphia for a while. He needed some help with design and with product. He decided to bring me over to LA at a moment’s notice to get help and restart the company and figured out what product to build. That was the beginning. Now, we’ve built the company to a point where we have about 22 people. Everything is amazing.

Suzanne: When you came onboard and did this restart, did you distill it down to the two of you and start from ground zero?

Jacobo: There was about four of us.

Suzanne: Four.

Jacobo: There’s a couple of engineers and yeah, we pushed restart and we cannot change direction, the famous term pivoting in tech, and restart again. We figured what the market needed. We spent a bunch of time researching. Through him, we had access to a few high growth technology companies that we thought would be the ideal candidate for early adaptors. We went out, talked to them and we figured that onboarding and the beginning of the lifecycle of an employee at a large company is, there was a big gap. A lot of the attrition turnover started to happen then when people felt unattended. They didn’t feel engaged. We thought if we could build a product for that, it could be very successful.

Eighteen months later, the company has grown. We’ve got clients. We realized that there is indeed a gap in the market especially with millennials that tend to get bored pretty quickly, that the idea of keeping somebody engaged, keeping somebody productive and helping them understand how to communicate with their team, how to do their job better, it really helps keep them around but it also helps eventually the company be more productive as a whole.

Suzanne: A lot of the people that I speak to, and I put myself in this category, arrive at product management through accidental tourism a lot of the times. Maybe not. Maybe some have started in marketing and found themselves realizing I’m doing a lot more product management than I am doing marketing per se. You have actually a formal background in product design. Were you always obsessed with product … Did you just come kicking into the role and say, “I am going to design and build great products”?

Jacobo: No. It wasn’t actually. It was very intentional. I always figured that a technical background would be very helpful if you want to stay somewhere in the technical field or a design field. Engineering for me was the natural undergrad. I figured if I got that technical background, then I could explore a more creative master’s degree or a more creative job or more creative experiences. If I did have that, that would help me really frame and understand better how to work conceptually.

After my engineering degree, I thought, well, now I have to learn how to design because there isn’t a lot of creativity in engineering degrees. I can tell you that. I went to design school. That was incredible. Getting hands-on experience, getting to prototype things and build and design and iterate, it was amazing. I think to me, it was always going to be close, being close in product. What I arrived at, it doesn’t matter if it was going to be software, if it was going to be a physical product, a consumer product, an enterprise product but I always wanted to be that liaison between the technical guys and the creative guys. I think it’s a very interesting place to be.

Suzanne: What’s the coolest product you had a hand in designing?

Jacobo: Wow. It was actually back in engineering school. My thesis project for my degree was hemp bicycles. I used a process called resin transfer molding where I combined soybean oil resin and hemp fibers. I influxed the fibers with the resin and I created bicycle frames made out of hemp. It looked very cool.

Suzanne: Can you fold them up? How tall are they?

Jacobo: No. They’re actually fixed and they’re very tough. They’re very durable. The idea was that it’s a fairly easy process and it doesn’t require a little training or a little machinery. It’s something you could easily outsource into developing countries especially because hemp just happens to grow in a lot of tropical developing countries. I figured, well, if we can provide those people with a means of developing their own tools, they’ll be able to actually create a sustainable economy as opposed to us funneling funds and doing things for them. That was the idea. That was pretty cool. They looked amazing. They looked beautiful.

Suzanne: You’re in software now. On your LinkedIn profile, you demonstrated a few of the products, the physical products that were part of your past. I guess people can go and look you up and see all of these things for themselves but I wonder, do you ever feel like it’s not as exciting? I mean interfaces are awesome. I love it but hemp bicycles sound pretty damn cool. Do you ever have these moments of going, well, electrons, you know, you can’t touch them. You can’t see them. You can’t ship them to developing countries practically speaking like we’re talking about. Do you miss that part?

Jacobo: I do. I think there’s a component, when you study design, it’s very natural to be able to touch and play with things. When you work with software, that’s somewhat removed. It’s a little more abstract, a little more conceptual. One of the things, one of the common threats that I think will always stay with me and I’d love to stay close in my career is the human component. I think human experiences and human behavior are two interests of mine. When you build a physical product, human experiences are very much in your mind. When you build a software product especially for us where we’re trying to essentially deconstruct human behavior, analyze it and then be able to improve it, we’re very close to that psychology. Yet, I agree that you don’t get that aspect of touching and playing and prototyping as much. You did get other things. You get scalability which is much more difficult with physical products. You can touch a million people with a piece of software in a second. For me to manufacture a million bicycle frames would take years or months and a little machinery and little processes. I think it balances out nicely, the ability to impact large numbers of people with the other side which is a little more hands-on but also at a much more scale.

Suzanne: I was teaching a product bootcamp this past weekend and one of my students was very much from the manufacturing world and was very much wanting to gain skills but apply them in that space. We were talking. You brought up the term pivot, right? These are all the terms that are now available to us. I like to call attention to that. We didn’t have those terms. They weren’t readily used. The other one that we talked a lot about and that gets misused tremendously is minimum viable product. We were doing an introduction to the MVP and some of the classic examples that we’ve all heard about was sort of all this concierge model, landing pages. He asked me what case studies exist for an MVP equivalent to physical products. I thought short of just simply prototyping something which is not really the same as an MVP … I mean an MVP, at least for me, isn’t just about building the quickest thing or the first demonstrable thing. It’s about building the thing that proves viability in whatever you’re trying to determine is or isn’t viable. What do you think about knowing physical product? Is there a way to apply MVP concepts in that space, do you think?

Jacobo: In physical products or in a software?

Suzanne: In physical products.

Jacobo: Yeah, absolutely. First of all, that term is the bane of my existence being a product manager.

Suzanne: Do tell!

Jacobo: It’s not always the one thing you want to hear about but absolutely. The way I always look at it is what is the smallest thing you can build, the most simple thing you can build to prove the core concept. If you’re thinking about building a product to solve a specific problem, what is the one thing you can do that if it doesn’t solve the problem entirely, it helps people picture or get the first hint at how their problem is going to be solved down the line?

With physical products, I’ll give you the example of the hemp bicycles. In an ideal world, the whole frame, the whole bicycle will be made out of hemp. When you put it out into the world, the only thing you got to do is attach a couple wheels, a chain, a couple handle bars and a seat. One of the issues I ran into is structural integrity. If you want it to be able to join all the different tubes in the bicycle using hemp, it’ll require a lot more precision in the way that you want the fibers, et cetera.

A little shortcut that I took was I made the joints out of steel. I created forming joints which is where the bars joined in the bicycle in their highest stress points mechanically. They’re fairly easy to manufacture, the task thing pieces. They can be manufactured at scale very cheaply and so I used that in the first version of the product. Now, what that helped me do is it helped me put together an actual bicycle that people could use and touch and play with but at the same time, I could show them too that there were hemp bars there. Even though the whole bicycle wasn’t made out of hemp, they could see it, they could touch it and they could use it in the same way that they would use a normal bicycle so to start helping prove the point. You’d take the first step and then, from then on, it’s how do we improve from here. The whole process is sustainable. The whole process can be outsourced to people, to low skill labor. That was the idea, I think, absolutely exists. It’s just a matter of distilling it to the simplest, simplest terms.

Suzanne: And maybe not using that terminology?

Jacobo: That’s right.

Suzanne: I have to go back. Now, I said I like the conversations to be organic like hemp and you said that term is the bane of your existence. Why?

Jacobo: That’s right.

Suzanne: Eric Ries, if you’re listening …

Jacobo: That’s right. Yes. Look, the thing especially with startups, larger companies are a little different, you’re always under resourced. You’ll always be playing catch up. If you don’t like that, please don’t join a startup because you’ll always have more things to do than you can do. Especially when you’re a product manager and you become the facilitator between many different parts of the company, a lot of your job is prioritizing. If the house is on fire, what is the first one we need to put out? I’m not going to start thinking about the furniture that I’m going to put in the room once the fire is out and I remodeled the house. The first thing I have to think about is how to put out the fire.

With MVPs, it’s a little bit about that. It’s clients always want more things that you can offer them. The industry always wants more than you can develop. Trying to identify what those things are and what you can do with the people that you have, it’s an art. It’s an ever growing top skill that you have to develop. I agree. I think we should find a better term.

Suzanne: One of the things that I’ve seen … I joked Eric Ries if you’re listening, I think that the earliest iteration of MVP was this is an experiment and so, when you apply that more broad label of experimentation, it really frees it from the form of product at all. A lot of great experiments that people smarter than me conducted to prove viability, whether growth viability or value viability, weren’t about the product at all. They were just about clever ways to poke around at where there was pain or opportunity or something broken. Now, people are talking about MVP interchangeably as your beta built or your minimum marketable product which is a very different concept. One is, what’s the minimum level of quality and polish we need to get this out the door and not have egg on our face which could be a very different concept and a very different level of complexity and architecture and time spent? Certainly, I try to bring back that concept of this is an experiment. How do you cobble together a few ideas much like how do I demonstrate hemp knowing that I can’t get all of the pieces just right but if people can see hemp as a bicycle, then I might be onto something.

Jacobo: Of course. One of the beauties of software is that a lot of the things that we build, somebody else tried to build before. It might not be the 100% solution of what we’re trying to build but it might be 50% or 60%. A good example, I’ll tell you something that I was trying to do recently. I was trying to think, well, I have all this network of people that I interact with. I have friends. I have acquaintances. I have different people that I know. My network is spread across many different platforms. It has become very difficult for me to be able to keep up with all of those relationships effectively. I thought, well, I wish I had a product that helped me do that. I wish I had a product that was like my brain outsourced and help me keep up with those relationships but it would take all these things to build. I’m starting to think about the technical aspects of it like architecturally, it’s this and that. Then, I thought, hold on a second. What if I can just go out and look at three or four different free tools that do the different aspects of what I want to do and I’ll just find a way to combine them. The amazing thing with software is that you can do that. You can also do that with consumer products. You don’t have to reinvent the wheel. You have to find different products that do similar things or that do what you’re trying to do to a certain degree and then you tinker. That’s part of the process. To me, it’s actually one of the most exciting parts of the process, the beginning stages.

Suzanne: I think also what you’re feeling into a little bit is never to underestimate the importance of pre-selling or actually having a plan for how you’re going to … Running a software company, we get entrepreneurs all the time. “Could you just build this for me for free? I don’t have any money right now but I just know that this idea is so good that once it’s out there, it’s going to be successful.” To them, I always say, “I already know how to execute. What I don’t know is what your ability to create effective acquisition channels, create a compelling marketing strategy and actually build the business are. I can’t recover those hours based on …” This is the myth. If you build it, they will come. I think about the tinkering, where I’m going with that is there’s a lot of precedent, for example, for buying product that already exists, slopping something over it or not even, just distributing it for a while and trying to understand the market that’s already there and then looking for, “Well, if we could improve this product, what would that be like for you, Mr. Consumer, Ms. Consumer?”

Ok. Tell us about Yoi. What does it do? Who is it for? Should we buy stock now? Those are my-

Jacobo: You cannot buy stock just yet. Yoi is a product that essentially helps companies develop and grow their people. We work with very, very large companies, tens of thousands, even hundreds of thousands of employees. We’re keeping track of how people grow and how people develop and how well managers are helping employees. How the machine works, the people machine works gets very complicated when you’re in 72 countries, 100 countries and you have hundreds of thousands of people and tens of thousands of business units. It’s difficult.

Even within the smaller companies, for management to understand how different employees work and what things work with them and what set of management styles are better than others, it’s not always so easy. As you know, one of the bigger issues in organizations of any size is communication and how you distribute knowledge across the organization. What we do is we follow a very simple … The product follows a very simple process. It’s based a lot in what you can find in McKinsey’s research in terms of people management.

At first steps, we have data gathering, we have analysis, we have insight and we have action. It’s almost like an ongoing process that feeds into itself. We think our hypothesis is that in order for you to help people grow inside of the enterprise, you have to understand who they are and how they behave and how they perform. You have to analyze that data. Then, you have to surface insights in many different ways. It can be visual dashboards. It can be specific nuggets of information to the right people.

Then, you have to be able to drive action. Once I know what I’m good at and what I’m not good at, let’s make sure I can improve on those things that I’m not so good at and take action and then, measure it again. You’re on this ongoing cycle that we believe helps people become productive faster but also be more engaged and understand better expectations and how to communicate and work with people and with their managers. We can do that for a small company of 10 people or we can do that for a company of thousands of people.

The idea is that if you’re able to … Reid Hoffman writes about this in his book, The Alliance, is that the way that the workforce is changing, the idea of staying in the same company for 25 years like our parents did, it’s not so current anymore. What you need to do is to be able to set expectations what you’re going to be doing in that company and in your job and also what you’re going to get out of it as an individual.

Very much in the future workforce, it’s going to become about growth and about development and about what skills they can gain out of this opportunity and what I can provide to the enterprise. Our product tries to help facilitate that growth. We’re in a bunch of companies already. I can’t really say the number but pretty successfully. The idea that you can understand human behavior and human performance and improve it is something that is very exciting.

Suzanne: Is it challenging to sell to enterprise level customers as a company of … You said now you’re 22. Before that, you’re probably 16. Before that, you were six. Do you have to do a lot of puffing out of the chest and making it seem bigger or has enterprise come around to this idea that small and nimble can be something reliable too?

Jacobo: That’s actually a very good question. Both. Fast growth technology companies like Facebook, eBay, LinkedIn, the ones that we all know are really trying to drive that change even though they are behemoths. They’re massive companies with people in all countries. They really try to maintain that core startup structure and that has really helped developed the different ways in which people are managed within the enterprise. There are also companies that are lagging behind but I think there’s definitely a sentiment going around where companies are trying to update themselves and be able to implement some of this new thinking.

It is challenging. Selling to enterprise is very challenging especially to large companies. The sales cycles are very long. It could be up to a year from first point of contact to actually deploying new product. There are a lot of gatekeepers. You have to sell many, many times within different units with different people to be able to get your product in. Small startups are more challenged, both research constraint and also funding and the capacity to be able to do things like compliance and IT security and things that are also present at smaller companies that other encumbrance in the market already has set up and have huge department dedicated to that.

We also move very fast and we’re able to adapt to circumstances and requirements very quickly. We try to be very hands-on with our clients. I think they really, really like that. They appreciate that when they come to us, we’re able to respond within a few weeks and have what they need very quickly while if they work with the Oracles or the SAPs of the world, it could take months for them to get what they want.

Suzanne: Right. It would be like looking in a mirror for them. We’re already slowing up ourselves. The last thing we need is another slow partner moving at our pace.

Jacobo: Exactly.

Suzanne: Very interesting. I noticed that you bulleted some of the core responsibilities of your role in your LinkedIn profile. One that I plucked out was managing the product roadmap. What do you think is the hardest aspect of roadmapping as a core function for product manager? How do you combat that?

Jacobo: That’s really interesting. It’s something that people look at it sometimes from the wrong angle. Product roadmap is a lot about what’s happening in the industry and what’s happening with trends and where things are going and not so much about who you are right now and what you’re currently doing. For me, one of the main things that I have is I’m a voracious reader. I constantly, constantly read. I read hours every day. I have a good understanding of all the different players in the market and I also understand where the market’s going and where the trends are going, how has it evolved from the past 20 years way before I was in here.

I think that gives you a perspective and it gives you the ability to understand how the chess pieces are going to move and what are some of the things that are likely to come in the next year or two years, five years. In terms of the market, that’s one thing. Then, another different avenue is people. How are people changing? This year, actually it was 2015, millennials became the largest workforce in the US. That’s only going to get bigger and bigger. Younger generations operate and connect and communicate very differently, as you know, than older generations.

Understanding how those people will interact with your product and what the requirements and expectations are going to be, it’s very important. It’s less about what you have currently and it’s more about understanding where the world is going and how you’re going to be able to keep up with it. It’s actually one of my favorite parts. It’s very … Playing and trying to predict the future is a very exciting thing.

Suzanne: Do you have any particular tools that you like or just sort of a crystal ball affixed to your desk?

Jacobo: It’s gut. It’s mostly gut. If someone comes and tells you, “I am absolutely certain that the future’s going to be that and chatbots are going to be the biggest trend in the next five years. All the many conversation and UI is going to die,” and all these different things I was trying to hear, I think it’s a full scam. We don’t know. We have different degrees of certainty about different things but we’re not absolutely sure of anything. Understanding that and accommodating for that big percentage that you might get wrong, it’s an art. Again, you got to learn how to master that and get better at it every day. Luckily so far, we’ve been pretty good at figuring out what people want. We’ll see how that plays out in the next couple of years.

Suzanne: We were talking offline before about this project, 100 product managers that you were saying actually, there’s not a lot of resources right now online surprisingly. I said I think it has a lot to do with this kind of mystification of product management. Everybody talks about it. Nobody talks about it. None of our friends or family seemed to really understand what it is that we do. People don’t know how to sell it. They don’t know how to inspire it. I guess maybe this is two parts. Do you agree with that sentiment and what do you think is the most misunderstood aspect of product management as a discipline?

Jacobo: I think the number one … I’ll take one at a time. Number one, it’s difficult to explain because product management doesn’t have a concrete deliverable. When I told my parents I want to be an engineer, I want to be a doctor, I want to be a painter, it’s easier to grasp because it has this narrow definition where there is a clear deliverable and a clear outcome. If you’re a painter, you’ll paint canvases. If you’re a doctor, you’ll fix people. If you’re and engineer, you might work for Boeing and you build jet engines or you might work for Tesla and build wheels.

With product management, you’re not the guy building things. You’re not the guy designing things. You’re not the guy. You’re the guy thinking. You’re the guy facilitating. It really helps if you’re very good at languages. The reason why I say that is because engineers use a different language than designers do. Content does. The account management does. The sales does. You really need to learn how to speak all of those languages. You’re going to be in the middle of all those things.

Your job is, the most important thing in my opinion, is to be able to translate between them and to be able to help them communicate and understand expectations and also understand how to allocate resources and make, again, decisions based on what is the first room we want to put out. If the whole house is on fire, I get to pick. It’s a difficult thing to understand but it’s also a difficult thing to explain. It hasn’t been easy for me to be able to communicate that to people who are not in the field or that are not technical. It’s a very exciting job. You don’t get a little of the glory but you do get a little of the action. That’s exciting.

Suzanne: That’s going to be your block quote, by the way. To use your analogy, and I agree wholeheartedly about the translator concept, which language is the hardest to learn in your experience?

Jacobo: The one that you’re least familiar with. For me, being a non-English native speaker, I think content and how to build content, there’s so many nuances into how to communicate things. There’s so many different layers when you write a question for survey or when you write a task for someone to do. It’s very complex and it has a lot of different parts.

Growing up as an engineer and being educated as an engineer and then being educated as a designer, I’m very, very familiar with those two things. I have a great interest in positioning and branding and how to communicate things but content to me is a mystery. I so admire the people that can do that. By using a few words, they can really convey so much and they can persuade and influence people to do certain things and to answer things differently. When we run A/B tests for different piece of content, asking a question one way or the same question in a different way, it yields completely different results. I haven’t really grasped that but hopefully, slowly I’ll get more and more of it.

Suzanne: You need the whatever the product manager’s equivalent is at the Oxford English dictionary. The content manager’s bible or something is yet to be written. In fact, they’ll give you the first chapter if you just give your e-mail and sign up to this mailing list. It’s our first free chapter.

You mentioned, and I was excited to hear this, you guys have a bunch of general assembly graduates.

Jacobo: We do have actually a former HR lead general assembly. We’ve hired a couple of designers from GA and I think we might be bringing in a … Don’t quote me on this one but I think we might be bringing in an engineer as well. We’ve been part of many … I don’t know how you guys call them when there’s a launch party and all the graduates are there and you can go in and meet them and look at the resumes or something. We’ve been to a couple of those events. There’s some great talent.

Suzanne: This is it. Yoi is living testament to the fact that there’s opportunity for GA grads who commit to the curriculum and come out on the other side as part of the alumni.

Jacobo: Absolutely.

Suzanne: I have the utmost respect for the brand and the work that they’re doing. If you were to offer advice to a recent graduate of product management, what would you tell them? They’re coming to you. “How do I get a job?” The age old, “I have no experience. How do I get experience? Will you hire me? I went to GA.” What would your advice be to that person?

Jacobo: I think it’s interesting because obviously, there’s a background to that which is when you go to a place like GA, it’s usually because you to try learn a trade that you perhaps haven’t learned before, right? There are other people out there that will have engineering degrees and that will have design degrees and will have all of these different experiences. That, on paper, might sound better and more qualified. However, there are a couple things that anybody can do and I’ve done myself in the past to be able to access an industry that has competition but that also you don’t, on paper at least, you don’t have as much experience as the guy next to you.

The number one thing is learn it. When I’ve interviewed people, I’ve chosen the capacity and the desire to learn above experience. It might be somebody that, although as not as qualified, has so much thirst and so hungry and really, really wants to learn what they’re about to do more so than somebody who has years of experience but that they feel they know more. Especially working with human capital, I can tell you the people that have that thirst and that desire to learn will grow much faster and will be a much better addition to the team than those that feel that have already learned or they’re more seasoned. At least in our experience, that has worked really well. That’s number one.

Number two is something that I’ll talk about an example that you and I have today which is before you came in today, I e-mailed you and I said, “Look, are there any questions that you would want me to know in advance so I can do some work and provide you with better answers when you come in?” I think that small nuance, that ability to say, “Look, you’re coming in. This is going to be an interview. If you tell me the questions that you’re going to be asking me, I can do some research. I can do some work so I can be of better service to the people listening,” that small thing I think can be very valuable.

I’ve seen it in some people. In advance, they’ll come to me and they’ll say, “Hey, I was looking at your website. I was looking at the product and this is something you can do. This is something you can improve on.” I was shocked. I thought it was amazing. That really, really helps somebody differentiate themselves from the rest.

Suzanne: What does it say about me that I shut your request down and said, “Don’t worry about the questions. Just be there on time and be prepared”?

Jacobo: I think you wanted me to improvise.

Suzanne: Here’s the theme and by the way, this is … You’re a journalist yourself, right? You’re a contributing author for Huffington Post which is-

Jacobo: I try to be as much as I can.

Suzanne: You must know on some level even as you’re saying that that in journalism, you want that room for the conversation to unfold organically. You’re an intelligent guy. You’re articulate. You’re polished and I want that room for the element of surprise so that something amazing might erupt and for all of us here, the great value of this conversation will never happen again because it wasn’t planned.

Jacobo: Exactly. It wasn’t prepared. There’s a great analogy. One of the big discussions that happened today with artificial intelligence is that we’re likely to miss some of the natural things that happen with people which is how we make mistakes and that we’re imperfect and that there’s no way for us to answer the same question the same way twice. There’s beauty in that. When each of us write, when each of us communicate and when each of us showcase ideas, talk about topics that we’re interested in, there’s so much nuance that comes with the imperfection and the opinions and the bias that machines will struggle to replicate. There’s beauty in that.

Suzanne: I’m reminded of there’s a short story, The Machine Stops, E.M. Forster. Do you know it?

Jacobo: I don’t think so.

Suzanne: It’s futurism and it was written in the ’60s, I think. It was set in a world far beyond our time, a little probably time wise before 2016. In the ’60s, they thought that robots were going to take over way earlier than they have. The fundamental premise was in this time, we’ve all moved into our own self-contained little pods. We communicate through screens and that’s it. In some ways, if you think about the way that we’re using technology in social, some of that has manifested. People don’t go out. They just sit on the couch. “I’ve got all my friends right here. I’m Snapping. I’m doing this.”

The story though, is fundamentally just about a boy who misses his mother and that sort of path back to human connection. You brought up humanism early on when you talked about your approach to design. This is another belief system that I share, my business partner and I share. We talk a lot about software, that human element. I think even in workflows, the best workflows are the ones that take the path that you already walk and then make it a little faster or a little more fun or a little more seamless. The technology doesn’t interrupt you.

There’s a component of the humanism that it’s … I don’t know. It’s present. It’s not present in the way that it interrupts your focus but that it feels organic. Organic is the word I guess of today. We’re getting way more philosophical than I thought … See, this is … than even I anticipated. I didn’t have that planned for.

You said you’re a voracious reader. You mentioned The Alliance already. Any kind of two or three must-read, you want to be in the space, you want to do well, you want to know the new, new thing, you cannot not know about it or blogs or podcasts, anything you would recommend?

Jacobo: Gosh. That’s a huge question.

Suzanne: Because I’m asking you to limit it. It would be easy if I said give me your top 100.

Jacobo: This is how I react every time that I have to prioritize! For somebody in the space, I think there’s a great book actually and a great man that I think has done a lot of work into the psychology of building successful products. His name is Nir Eyal. He wrote a book called The Hook Model. He talks about how there’s certain steps to be able to build a product that is habit forming. He wrote that book with Ryan Hoover who was the founder of Product Hunt. I think it’s a very interesting book that helps understand how the psychology works and how to build successful products, products that people love. If you take that and extrapolate it into some of the most successful social media products that scaled very vastly, you’ll see that model implemented in them. The Hook Model is a great book. The Power of Habit is a fantastic book as well.

In terms of product management, there are great podcasts. There is the StartUp Podcast. There is the Product Hunt podcast that you can listen to. In terms of daily reads, I read Hacker News. I read Sam Altman’s blog, Sam Altman, the president of Y Combinator. I read Paul Graham’s blog. There are some really, really great content out there. If you go into Andreessen Horowitz’ podcast as well, they talk about technology and the future of technology and where it’s going.

In terms of product management itself, it’s an interesting thing. I think one of the greatest things that you’re doing right now, it’s getting out of the minds of the people into a form that we can all consume. Although there are different sources for a lot of the chess pieces within a company where you’re building a product, there isn’t a lot of resources to teach the chess player how to move all those pieces. I think it is really valuable to condense that knowledge and to be able to aggregate that and present it in a way that we can all look at it and consume it and even reference it every day to keep learning. I’m very excited to see the results.

Suzanne: Thank you. I appreciate that. This is my last question for you, by the way. Heads up, last question. You muttered under your breath before you panicking about prioritization. It’s just a little leaky data moment.

Jacobo: It was a big panic.

Suzanne: One of the sound bites that I use, and I say this to clients all the time, if everything is important, then nothing is important. When I ask you to prioritize the tickets, don’t put ones next to everything. Do you have a sound bite of your own that’s been kind of you, we’re in the meditation room, a mantra if you will that sums your perspective on life or your perspective on business or to something that gives us a little knowing to you as a person?

Jacobo: Yeah. There are so many. I keep a record on Evernotes of all my …

Suzanne: This is a technology product.

Jacobo: Oh my gosh, yeah. Evernote is a life saver. Gosh, I want to meet Phil Libin one day. What a genius. I think there’s a concept that I really, really like. I think Steve Jobs might have mentioned this in some interview which is we all can connect the dots backwards but we cannot connect the dots forward. It’s something very interesting to me to have the ability to, and it’s fundamentally human, to have the ability to connect different pieces. You don’t just become very, very good at the one thing. Being multidimensional individuals, I think it’s really interesting that we can become very good at the intersection of many things. If you ask anybody, what is the number one thing, the number one interest that you have, a lot of people will struggle and will tell you, “Well, I like many things.” I’m afraid I’m going to be telling my generalist that I’m never going to be the guy for that or I’m never going to be very good at one thing. I think we should be less afraid of that and we should be constantly thinking about how everything in our lives, everything that happens, all the experiences that we have and all the knowledge that we have can be connected into different intersections.

Very much like our brain, like a neural network, there are many branches and there are very many nodes where things get connected and synapse happens. Knowledge works the same way. You take different concepts and so you create something new. That’s what happens with technology and what happens with products. It’s difficult to reinvent the wheel. Tesla is using technology that was invented 100 years ago. They just managed to put it in a beautiful shape, in a beautiful car with newer parts and with big screens and suddenly, it becomes something new and amazing and life changing for many people. That capacity to change, that capacity to connect different pieces, it’s something that I’ve seen in many, many successful entrepreneurs. Like I said, we’re multidimensional so why not exploit that?

Suzanne: Beautiful. We might have tough time putting that on a side of a mug just to see … Your famous quotables will look more like an eye chart when you make it to Startup Vitamins.

Jacobo: That’s part of the art, right? Distill it.

Suzanne: Jacobo, thank you so much for your participation. We’re so fortunate to have you be part of this, whatever this is that we’re building. I don’t know but I think so many people, myself included, will benefit from these insights you shared so thank you.

Jacobo: Of course. You’re welcome.

In this episode:

- Where do startups go wrong with implementing OKRs

- Can OKRs really scale for enterprise?

- What are pipelines and how do they change the way we think about product roadmaps?

In this episode:

- From retail to product management

- Why relationship building is the number one required skill a product manager could have

- The value of having confidence with humility

In this episode:

- Establishing a clear vision of your career path

- Using metrics to answer burning product questions

- What product managers can learn from biology